Tatar and Kyrgyz Traditional Music: A Research Paper by Courtney Van Cleef

*DISCLAIMER: I did not include my bibliography nor are my sources cited in this online posting! Although I organized the research in a cohesive manner, the information presented is not all my original work and should be reviewed with educational purposes in mind.

Several lifetimes of research would not be enough to cover the history of Russia’s rich music culture. In part, the process is complicated by the many ethnic groups that fall or have fallen at some point under the umbrella of Russian borders and/or occupation. It can be easy to immediately consider only the cultural history of Muscovites; however, this way of thinking ignores the millions of ethnic Russians in all directions beyond the capitol. Furthermore, there are regions beyond current border lines whose inhabitants represent cultures forever changed by soviet influence. One such region includes the Tatars (an ethnic group extending from Tatarstan in the Volga region of the Russian Federation to the bordering country of Kazakhstan) and the Kyrgyz (most of who currently reside in the neighboring Kyrgyz Republic). Together the Tatars and the Kyrgyz stand as a unique bridge between eastern and western music traditions. In many ways, including a largely pentatonic tonality, eastern style instruments, and Islamic religious influences, the music is firmly rooted in the ways of central Asian life; however, evidence of the consequences of Soviet occupancy , for example the appearance of “modifications” to otherwise ancient instruments, suggest a nod to the west. This paper aims to take a focused look at the musical practices that define the Tatar and Kyrgyz people.

Before delving into the specifics of Tatar and Kyrgyz music, it is sensible to address the forces of time and Russian contact. Although the Kyrgyz were somewhat included in the Russian empire at the end of the 19th century and later became a full republic of the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, Kyrgystan is farther removed from Russian culture and influence is more subtle. More widespread Russian influence is naturally found in Tatar music as even today a significant portion of the Tatar ethnic group live within the Russian Federation’s borders. Craig Macrae writes in his review of the Luman Seidjalilov: Legend of Crimean Tatar Music recording, “Russian influence dominates the instrumental aspect of performance [including] the violin and accordion accompaniment, the ubiquitous minor key, and the nostalgic mood”. In regions on the fringe of the Moslem centers of the Tatars, for example the Tatar-Mishars living in Russia’s Volga area (also referred to as Volga Tatars), we see genres such as wedding songs. Ceremonial songs were not acceptable per Islamic law and thus one is left to conclude that they are only found in Russia where Eastern Orthodoxy is the more common religion. Kazakh musicologist M. Nigmedzianov is careful to make the distinction that although the more ancient music of the Kazakh Tatars is closer to the heritage of the Tatar-Mishars “young people choose to ignore it” suggesting that the more modern generation of Tatars within Russia are moving further away from the bonds of tradition. Despite the seemingly overwhelming Russian presence, researchers generally agree that in reality ancient traditions continue to dominate the music traditions of Tatar peoples. László Vikár in his paper on Tatar Folksongs observes that “around the mid-Volga region, the predominant ethnicity is the Kazakh Tartars” and that “this influence has always remained stronger than that of the Russians who found the Soviet state”. An immensely positive byproduct of Russian contact was the encouragement of written records of music previously kept alive only through oral passing from generation to generation. For example, the “Traditional music and musical instruments of the Kyrgyz” website credits Russia by saying that “it was only when [the Kyrgyz] came into the Russian sphere of influence that their traditional music was written down in any form, let alone in musical notation”.

The simultaneously eastern and western features of the instruments seem to support the theory that the Kyrgyz and Tatar region’s central place in Asia effectively makes it a bridge between the two worlds. A few examples of string instruments include the Komuz (also called a “Chertek” meaning “striking) and the Kul Kyiak. The Komuz, played by a musician called a Komuzchu, is similar to a lute in that it is played horizontally and is plucked. The instrument is made from apricot wood and only three strings. The Komuzchu is usually sitting, but he can be standing. The online Encyclopaedia of Britannia makes the special distinction of the Komuz as the instrument of choice in the development of rare polyphonic tunes called “Kernel Tunes”. The Komuz goes by several different names in other central Asian cultures, for example the Kazakh Tatars refer to this instrument as a Dombyra.

The Kul Kyiak is a bowed string instrument with two strings made of horsehair and a “jaa” or bow made of Tabylay (a thick mountain plant) and also strung with horse hair. This instrument has a close relative to the Kobyz played by the Kazakh Tatars. The uses of horse parts in string instruments of the Kyrgz and Tatar alike seem to reflect a closeness of the equestrian focused Central Asian cultures. The bow is typically cupped from below. Modern Kul Kyiak and Kobyz instruments typically use four metal strings, likely in attempt to more closely relate to the western violin. These modifications appear around the 1930s during Soviet occupation by Russia. Vikár suggests that the introduction of four strings by the Russians is likely the cause for the prevalence in Tatar songs shifting a repeated line to the lower fifth. As he puts it “it is easier and more natural for the singer to repeat a line on the lower fourth than the lower fifth.

One must be careful not to confuse the Kobyz with the traditional Tatar instrument, Kubyz. The Kubyz, in contrast, is a reed-and-plucked instrument commonly referred to as a “jew’s harp”. It is a small instrument with a lyre-shaped frame that is held between the teeth and a projecting steel tongue that is plucked to produce a twang. Contrary to early research, the Kubyz is not an idiophone as it requires use of the performers “performer’s respiratory and articulatory organs”.

The Asa-tayak is an idiophone instrument that essentially comprises of a stick with various metal, animal bone, and fabric attachments. Unsurprisingly, these attachments are assembled with horse-hair, once more reminding researchers of these central Asian equestrian cultures. It is meant to be struck against the floor in order to generate noise. Although the Asa-tayak is found amongst the Tatar and Kyrgyz alike, the shamanic connotations make it far less common in the more heavily Islamic influenced Kazakh Tatar region. Often it is abandoned in favor of the Kobyz or percussion instrument.

The Kernei is a wind instrument specifically identified with the Kyrgyz as an instrument that announces the arrival and departure of official peoples (rulers of militaries). There are two types of Kernei including the Jez Kernei (made from brass) and the Muyuz Kernei (made from mountain goat horn). Kernei are unique in that they have remained unchanged from their original form. Although the spellings vary, creating confusion in research, the Kyrgyz and the Tartar share many wind instruments in common. Most of these instruments are a kind of flute that belongs to the Choor instrument family. The Bashkir-Tatar Kurai, a five- holed example of a Choor, is particularly conducive towards a pentatonic tonality as the five fingers make it possible to play two types of pentatonic scales. The notes in both scales combined spell out a major hexachord.

Tatars and Kyrgyz music cultures both boast of Akyns, or master improvisers, that resemble the European model of a minstrel. Akyns are most typically known for competing in Aytish during which two Akyns will accompany themselves on a Komuz (or Dombyra amongst Kazakhs) and duel in sung verse, each bouncing off the other’s words and ideas in rhythmic singing, chanting and exclaiming. A special kind of Kyrgyz Akyn called a Manaschi is tasked with the purpose of relaying the story Manas, the epic hero central to the culture of Kyrgyz peoples. Although women Manaschi are rare, they are not unheard of.

Yet another special kind of performer is the Kazakh Tatar Kuishi or the analogous Küü performer in Kyrgyz music tradition, who perform programmatic instrumental works called Kui (or küü) on the Dombyra (or Komuz). The Kui is approximately two minutes in duration and composed by the Kuishi himself. Although lyrics are not provided, it is widely accepted that the story line for each Kui are typically “so well known to the audience as to need no announcement or specially provided for listeners by the performer through a verbal introduction”. In addition to storyteller, Kui performers would also assume the role of entertainer by performing tricks such as playing the instrument in unconventional manner (over the shoulder, between the knees, etc.).

Vikár carefully denotes certain tonal and features that appear unilaterally across all genres of Tatar songs. Like the Kyrgyz songs, the overwhelming majority of Tatar songs are pentatonic with a mere ten percent instead falling into the sol-la-do-re or la-do-re-mi tetratony. Very few songs end on Re but when they do, they typically imply a closing Sol. Interestingly, the Re and Sol pentatonic scales are related in that both are without 3rds. Additionally while the Re and Sol pentatonic scales are considered by Mongolian folk researchers to be “truly ancient”, the Do and La pentatonic scales that do contain thirds are thought to have only evolved from western influence. Although large intervallic leaps are rare, when they do appear in the form of 6ths or 7ths, grace notes are placed between the notes in a way that aid the leap without “coagulating into glides”. A byproduct of pentatonic tonality, 4ths and 2nds are far more common than the strings of 2nds and 3rds observed in western major minor modes.

The primary song genre of the Tatars is the lyric-epic song called ozyn koi (also spelled uzun koj). Ozyn koi follow the traditional monophonic form without instrumental accompaniment. Even the addition of a choir is prohibited. They are typically without leaping intervals although they are often highly embellished with melismatic ornaments and rhythmic freedom. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia further defines the Ozyn Koi as having variable meter and asymmetric structure. Ozny Koi, sometimes referred to as the lyric protracted song, retain such extravagant freedom that Nigmedzianov notes performances between singers in the same village share “merely the same outlines of melody and rhythm while the words remain completely identical”. Vikár notes the necessity of a mature male voice in singing the Ozyn Koi. In addition to perfect pitch, and an ability to mold rhythm, the singer must also have an excellent memory in order to finish the entirety of the text. Vikár provides only one example of relatively short ozyn koi, “Kara Urman” (black bear), which would typically be sung by a woman. The words themselves are typically solemn and serious as they often speak of great persons and events of the past.

In contrast, the kyska koi (also spelled Kiska Koj) are generally shorter, light-hearted, dance songs with set metrical and rhythmic organization, absence of ornamentation, and a quadratic structure. Vikár notes that the syllables typically number 7-12 per line. He also makes the distinction that Tatars themselves are unclear how to classify Kyska Koi in relation to the Ozyn Koi from which they typically transition. Interestingly, the The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, tries to make the claim that Takmaki (or in Russian, Chastushka) are a subgenre of Kyska Koi due to their funny, jubilant nature. Vikár, however, aligns what he calls “tak-mak” with the song genre “Baet” because “both feature text in the first place and the role of simple melodies is secondary”.

Baet (also spelled Bait) belong to the next largest genre of Tatar songs, the Baity. They tell the stories of old men, thus it is no surprise that the words are the main feature. Four lines per strophe feature 7-8 syllables with each syllable containing no more than a single melody note. As previously alluded, these songs are typically sung by old men who Vikár observes “can convey events of the past most authentically”. Nigmedzianov adds that the Baity are typically written in a structure of arioso-recitativo. He also makes an intriguing distinction between Volga Tatar and Kazakh Tatar baity by noting that the Volga Tatar tendency to lyricize poetic images within the baet suggests a sort of unique blend between baity and the lyric protracted song, or ozyn koi.

The other main genre of Kyrgyz song, separate from the songs of the Akyn, is the ïr. Beyond that a “striking features of Kyrgyz vocal music is the ability of its finest exponents to sustain notes at full volume for a seemingly superhuman duration”, there regrettably seems to be little or no further accessible research on this particular genre. Based on similarities in instruments utilized and close proximity to the Tatar region, the ïr genre has a high probability of at least featuring elements of the discussed Tatar genres.

The Tatars and Kyrgyz represent only a fraction of Russian touched central Asian music and are undoubtedly linked to those cultures beyond the scope of research presented here (for example, the cultures of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, etc.). Furthermore, the uneven nature of readily available research in favor of the Tatars over the Kyrgyz portrays an inaccurate deficiency of Kyrgyz traditional music. Fortunately there appears to be an ongoing movement to create more written records. What makes the people of central Asia so peculiar and important in the history of our world is their special seat between the western reaching Russia and the east. Russian Imperialism and Soviet Occupancy in many ways disrupted the traditions of the Tatars and Kyrgyz and yet they also created a rare specimen culture that permanently falls somewhere between two otherwise separate worlds.

Unveiling Theoretical Techniques in Early Russian Music: A Research Paper by Courtney Van Cleef

*DISCLAIMER: I did not include my bibliography nor are my sources cited in this online posting! Although I organized the research in a cohesive manner, the information presented is not all my original work and should be reviewed with educational purposes in mind.

Many scholars will have you believe that the history of Russian Music before Glinka is sparse and ultimately insignificant. It is true that the improvisational nature of the Russian people’s folk music does not lend itself to the extensive documentation that we see in Western Europe. Furthermore, the ban on instrumental music in the Byzantium-style Eastern Orthodox Church in many ways retarded the rapid development of an instrumental body of work that would put Russia on the map. It was not until the 19th century that at last we begin to see the circulation of collected folk songs. Even today, case studies on the music of tribes located around Russia’s vast geography are not easily accessed beyond its borders. Nonetheless, one must recognize the deeply ingrained characteristics in the music of these ancient cultures on the composers that so define the Russian Repertoire. Indeed, the collections of songs compiled by Balakirev, Tchaikovsky, and Stravinsky, not to mention the countless references in music of Soviet composers such as Shostakovich, all owe to a deep respect of the music of the people. This essay aims to explore the theoretical techniques that characterize early Russian music. In order to comprehensibly cover the most important spheres in this genre, we will explore the folk song traditions of western Russia, observe the traditions of the Nenet people as a sample of Siberian traditions, and identify traditions in Russian liturgical music.

The largest a most diverse body of early Russian music is found in folk songs. These include but are of course not limited to byliny (heroic songs written of a type of Russian warrior, known as a bogatyr), historical songs, ritual songs, wedding songs, bytovye songs (written about Russian daily life), and lyrical songs. The songs were a part of everyday life to the peasants and are thus treated with a sort of reverence and seriousness. For example, instrumental accompaniments is simply not present as the Russians associate instruments with “light-hearted revelry” and consider them to be inappropriate in the context of the song. Furthermore, women are the primary vocalists to sing these songs.

Rhythmically, Russian music rarely conforms to a western style formation and thus bar lines serve little purpose. Whereas in a western country, the syncopation of the Bohemians or the rattle of the castanets in the Spanish fandango have become easily identifiable as distinctly belonging to these countries, the closest we come to a “Russian” rhythm lies in a vigorous three accented pattern found in a pliassovyia (dance song). In line with the treatment of songs as serious, it is not surprising that Russian dance songs are not particularly significant to the culture. In classifying the various types of Folk songs, scholar Emily Ahrens also notes the Bytovye as another type of dancing song with strong accents on the final beat and clearly expressed rhythms.

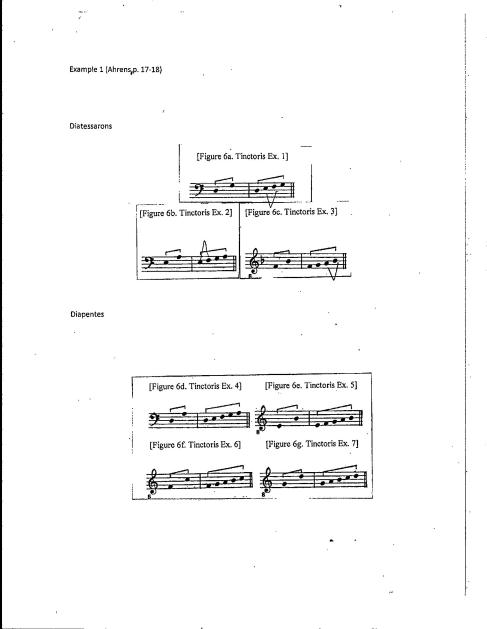

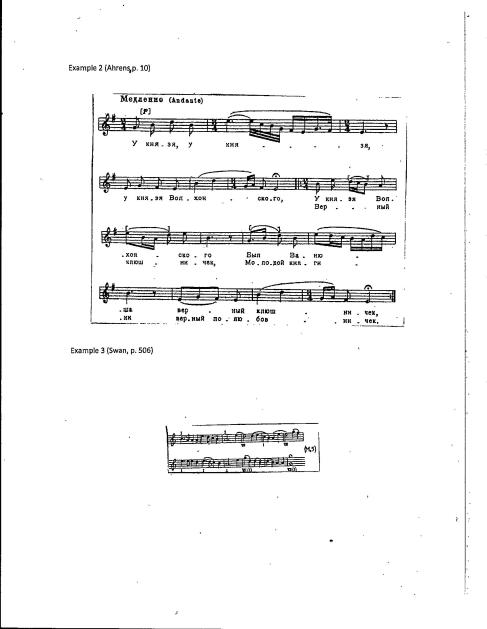

Harmonically, most scholars agree on the Russian folk songs being largely diatonic. In relation to choices of progression by the various voices, music historian Alfred Swan goes so far as to say that non-diatonic half-steps are utterly alien to the peasant vocalist. However, there are multiple arguments as to how exactly the music should be analyzed. Ahrens utilizes the Tinctoris treatise, De Natura et Propretate Tonorum in its discussion of the three types of diatessarons and the four types of diapentes, to explain the various pitches. Example 1 (Example 1) provides a staff representation of the various diatessarons that divide the octave by a fourth and the diapentes that divide the octave by a fifth, conveniently labeling them A-G. Simply put, the diapentes and diatesserons together form the scales observed. If we look at Example 2 (Example 2) we see that all pitches included are E, F#, G, A, B, C, and D range is from E4 to E5. Although the song begins in G and the “key signature” provided by the editor, Tchaikovsky, suggests G major, the fact that the piece ends on E suggests a different tonality. This is consistent with the Russian ideal of “peremennost” (or, mixing of tones) and its consequences stand at the crux of analytical debate. Using the ideas of Ahrens we can build a scale using all pitches by combining Diapentes D and Diatesseron B. This is considered authentic form as the scale divides the octave into a fifth on bottom and a fourth above with the first note of the octave as final and the fifth above the final as dominant.

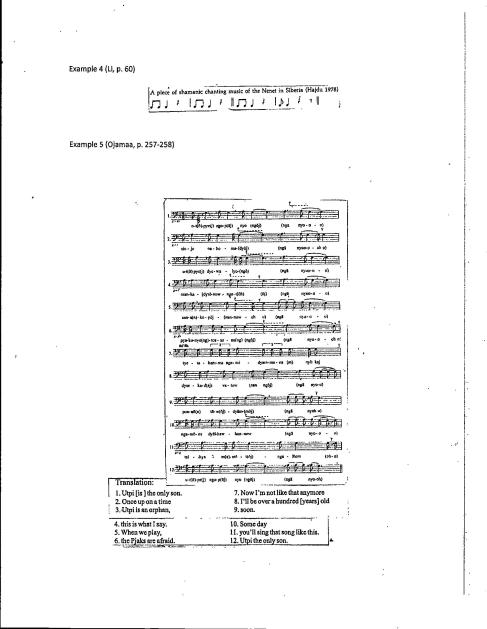

Swan’s approach to analyzing the folk songs uses the traditional church modes but accounts for the seemingly undulating major and minor tonal centers by speaking about “semi-chromes” where notes of the chromatic scale crop up in the course of the melody, but not successively. He proceeds to choose examples where he finds what he considers to belong to a specific mode, and then comments on distinct Russian treatments of these particular modes. For example (Example 3) in this excerpt we see what appears to be a portion of the song in a natural minor (Aeolian mode). Swan notes the Russian tendency in this particular mode to place emphasis on the VII degree, in effect implying a harmonization by a major chord. True to form, the excerpt ends on a G, and in the preceding measure a G major chord is clearly outlined. This supports Swan’s observation of the VII and its treatment in Aeolian form. Had we used Ahrens’ analysis method, we might have noted instead the G4-G5 range and then have chosen to combine Diapente G and Diatesseron A to account for all notes in the example (Example 1).

Additionally, there are distinctions to be found in the way that voices enter and harmonize. As previously mentioned, the songs were generally performed by women and thus we will often observe a solid middle range of pitches. Often a “precentor” or soloist will begin singing and complete a period of varying lengths. She will then be joined by a mixed choir that will, without fail, enter all at the same time and remain until the end of the song. Consistent with the mistrust of Russians for a regular or predictable beat pattern, the choir may not join the soloist on a strong beat and indeed could enter on what Swan describes to be a passing tone.

One example of a Siberian music tradition is that of the Nenet peoples. Nenets inhabit western Siberia between the Kanin Peninsula in the White Sea and the mouth of the River Yenisev. The population is small, only totaling in approximately 30,000 people, and is divided between the tundra (thus the term “Tundra Nenets”) and the taiga (“Forest Nenets”). The Nenet are largely herders of reindeer and as is common in such cultures their religion centers on rituals enacted by a village Shaman. An example of Shamanism affecting rhythmic tradition is frequent use of a Manchu-like “three-accented pattern” (Example 4), thought to bring good luck and fortune. The hierarchy of the Shaman and the central position males have in Nenet society account for the distinct difference from western Russian music tradition of women leading the songs. This may also account for the low timbre of notes in recorded songs.

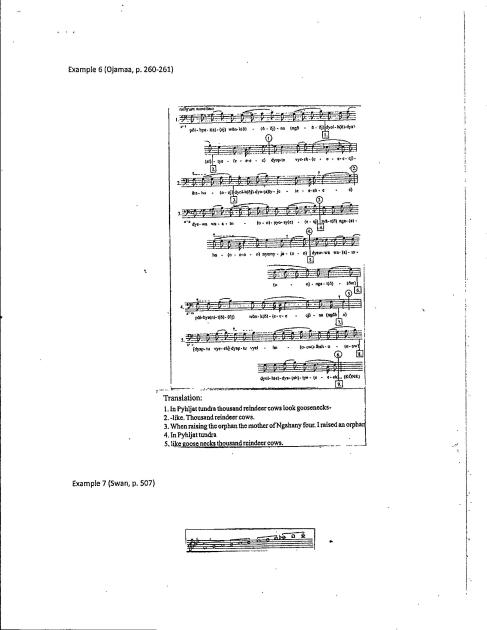

Nenet music is circumpolar in style and based on a trinity of singing sound, speech-like sound, and imitative sound. In Nenet music, the meaning of the text is of greatest importance in the song. In an interview with Juri Vella, a forest Nenet from Khanty Mansi Autonomous Region of western Siberia, he specifically notes that a singer may repeat a line that he feels the audience did not understand the first time. The singer will try to provide an explanation in the melody, thus the melody is retained but not in the same way as the first time. This, however, does not account for all rhythmic deviation in a melody. In Example 5 (Example 5) an examination of the text in line 7 does nothing to further explain the previous lines, yet it has a recitative melody and is performed ad libitum. In cases of melodies recited by Shamans as magical formulas, the songs adopt an entirely speech-like sound, imitating speech intonation.

The focus on the text leads to many rhythmic peculiarities, for example the text will often not line up with the melody. To this end, melodies can be placed in two categories. In the first category, a phrase is repeated without change and the melody is considered an equal-length composition. In the second category, the length of the melody changes each time based on the text. Vella comments that at times a message takes up more space than one line, causing the singer to “violate rhythm and speak in a hurry”.

Conversely, the text may be shorter than the melody and thus meaningless syllables are added. In Example 5 (Example 5), Line 2: kogda-to v proshedshchem vremeni nga nej translates to “Once upon a time nga neij” with “nga neij” acting as filler syllables. Meaningless syllables can also be greatly useful in joining 2 lines so that the song is rendered as one uninterrupted sentence. This technique is linked to Shamanistic songs as ritual dictates that interrupted singing can prevent a message from reaching the spirits.

There are also instances where the text continues past the end of one melodic line and into the next. The point of this practice is meant to encourage a sense of continuity. In Example 6 (Example 6), the word wyek-lhaho is broken between lines 1 and 2. A technical practice that supports this call for continuity lies in breathing. Vella comments that Europeans breathe when a line ends, but Nenets breathe at random places so that breathing does not mean anything”. Ojamaa claims this is only part of the truth as there are in fact cases in European art songs where the vocalist breathes in a place other than the end of a sentence, just as there are places where Nenet breathing is not arbitrary.

A final but nonetheless important section of traditional music can be found in that of the Russian Chant and its place in the Eastern Orthodox Church. This genre for a variety of reasons including an archaic notational system also remains the most elusive in terms of proper analysis. As stated by Schidlovsky, one discovers that “what might be called a “theory” of the music has to do primarily with questions of notation”.

Russian Orthodoxy arrived in Constantinople during the reign of Prince Vadimir of Kiev in the 10th century. Its point of origin makes it not surprising that the theory and notation of early chants were strongly influenced by Greek theory. Specifically the middle Byzantine notation classified as the Coislin System was used for notation, characterized by tonal range symbols, strokes, and special black symbols to indicate inflections of the neumes. This Russian kind of neumatic chant was thusly termed znammeny, from the word znamia, meaning sign or neume. The earliest readable chants to be found come from the 12th century. Unlike western chants based on scales, these early manuscripts of Byzantine psalmody and hymnody suggest an organization by a system of eight church modes (echoi) referred to as the Octoechos. The chants appear to be diatonic and unison. In Swan’s example of the liturgical scale (Example 7), we find the pitches F, G, A, B-flat, C, D, E-flat, F, G, A-flat, C. This means that in the lower octave there is a major triad F, A, C and in the upper octave we have a minor triad F, A-flat, C existing within the same scale. Swan’s point is that this is a commonality in folk songs and thus implies a link between the two genres. Unfortunately, the majority of these earliest texts no longer exist, most likely as the result of war and invasion of the tartars.

By the 15th century, a ravaged Kiev had sharply declined as a Russian cultural center and Moscow was on the rise. During the reign of Ivan the Terrible from 1533 to his death in 1584 we begin to finally see manuals called azbuki that explain the neumatic system. Azbuka developed in scope to include not only short verbal descriptions, but also the “razvody”, or explanations of the more complex notation through the use of equivalent, simpler signs. In the early 17th century, Ivan Shaidurov, a west educated monk familiar with Renaissance music of Western Europe, clarified znamenny manuscripts by introducing two improvements. The first of these changes included a codified scale system of the Great Russian Znamenny Chant by firmly establishing the number of pitches in the scale as twelve. He also introduced a system of red marks to accompany the black neumes as an indication of pitch, qualitative and qualitative inflections of the neumes. These red marks create a sort of “ladder”, beginning with a bottom rung of three pitches including Low UT, Low RE, and Low MI, a middle rung of six pitches including UT, RE, MI, FA, SOL, LyA, and a high rung of three pitches including High FA, High SOL, and High LyA. If we give pitch names to these syllables we are left with C-flat, D-flat, E-flat, C, D, E, F, G, A, F-sharp, G-sharp, A-sharp, confirming that the twelve pitches create a complete chromatic scale despite a missing TI (covered by C-flat).

The last significant reforms of the Russian chants appear around the 1660’s under the direction of Patriarch Nikon in his quest to reform the Orthodox Church. A third group of Symbols, Auxiliary Pitch Marks, were added to clarify the pitches with their tonal range signs. Nikolai Diletsky’s Musical Grammar, published in this era, not only helped explain these reformations but also encouraged western style polyphony (including clear tonic-dominant harmonic relationship). The reign of Peter the Great further brought an influx of French, Italian and German influences that obscured the techniques of the Russian tradition. On the subject of church music written during this time, Razumovsky notes that “not one of these works proved to be perfect and edifying in a church sense, because in each work the music predominates over the text, most often not at all expressing its meaning”. In the context of a culture that for hundreds of years did not allow instrumental accompaniment for concern that it takes away from the meaning of the words, this practice is in major conflict with the original traditions.

Uncovering the theory that is so deeply rooted in passed down traditions, compounded by sizable holes in the documentation of the earliest Russian music, is no doubt a challenge for modern scholars. The various collections of songs and the conflicting manner in which their notation is treated is a testament to the unique quality of the Russian song and its ill-fitting nature when explained with the much more easily accessible western theory. For scholars who seek to understand what makes the music of Glinka and beyond distinctly special, it is absolutely necessary and in fact exciting to dig deeper for more knowledge about how the people of Russia structured their own music theory. There is still a copious amount of research to be done, but studies on sub-cultures like the ones conducted of the Nenet people may be the key to finding the answers. Meanwhile, an effort by the Russians themselves to preserve their culture in performance and church keeps the repertoire in sight and encourages more study by musicophiles and musicologists alike. Perhaps in time, we will see a picture clear as that of music theory in Western Europe.

Fresh Squeezed Ballet

I was watching one of my new favorite ballets, Prokofiev’s Cinderella, when out of no where the composer pulls out what may be my most favorite composition of all time, “March”, from The Love for Three Oranges (see post: Prokofiev Loves His Three Oranges). It sort of took me by surprise and also confounded me as to why this quote appears in the middle of a totally unrelated ballet. The setting of this scene is an elegant palace style ball and all of the sudden guests are passing around oranges… bizarre. Only in Russia right?

I’ll keep looking for reasons as to why Prokofiev did this; however, I’m guessing it had largely to do with the wide popularity his composition gained him 20 years earlier in his career.

Here is video proof that I’m not making this up:

Cello Bonus* Rachmaninov’s Cello Sonata in G minor

I couldn’t sleep with the fact that I wrote an entire article about Rachmaninov but nothing about his greatest work of all, Rachmaninov’s Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 19! OK, maybe I might be just a wee bit biased…

Here are the notes I included when I performed this Sonata as part of my senior recital at Stetson University in May 2012:

Sergei Rachmaninov’s Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 19, was completed in November 1901 and premiered by the composer himself alongside cellist Anatoliy Brandukov (for whom he dedicated the music). Rachmaninov purportedly rejected the title of cello sonata as he viewed the cello and piano to be equally dynamic. Very often, the piano introduces a theme which is subsequently taken and embellished by the cello. As typical of sonatas in the Romantic period, it has four movements including a rich Lento – Allegro moderato, a fast paced Allegro scherzando, a sentimental Andante, and finally a triumphant Allegro mosso. Each movement contains a chain of melodies that focus less on thematic development than on the themes themselves. The success of the sonata was overshadowed by the acclaim of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No.2 which premiered in October of the same year. Nonetheless, the Sonata is considered one of the most important works for cello in the 20th century.

By the way, cello students learning this piece should give the music to their accompanists WAY ahead of schedule (I am talking months in advance). This work is a real doozy for even the most seasoned of players and they will need a lot of time/patience to feel comfortable in performance. You really have to take care not to be ridiculous with your tempos, lest you sacrifice your ensemble. This was all the information I could find given the tools available to me. What can I say? Enough said!

I will let the great Rosty and his pianist, Alexander Dedyuhkin, share this one. Enjoy!

First Movement:

Second Movement:

Third Movement:

Fourth Movement:

Bane of the Pianist’s Existence: Sergei Rachmaninov

This post, we will explore the life and times of every pianist’s worst nightmare, Sergei Rachmaninov.

Серге́й Васи́льевич Рахма́нинов, a.k.a. Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninov, was born April 1st, 1873 in Semyonovo Russia (picture a suburb of its parent city, Novgorod). A boy from aristocracy, young Sergei was not the kind to suffer want. Both Rachmaninov’s father, Vasily, and mother, Lubov, were amateur pianists; however, it was Mom who gave Sergei his earliest lessons (age 4ish). Granddaddy Arkady Alexandrovich Rachmaninoff recognized Sergei’s talent and contributed to his education by bringing in the famous Anna Ornatskaya to formally teach the piano to Sergei at the tender age of 9 years old. She remained with the Rachmaninov’s until they moved to Saint Petersburg where Sergei began lessons at the conservatory. This move marks an unfortunate time for the family. In addition to the humiliation of losing their estate in Semyonovo (due to Dad’s poor spending habits), a diphtheria epidemic killed his sister, Sofia. His parents separated shortly afterwards, leaving their three remaining children in Lubov’s custody. Sergei struggled as a result of these domestic trials and upon failing his exams in 1885 it was suggested to his mother that he be sent away to Moscow to study.

In 1885 Sergei made the move to study at the Moscow Imperial Conservatory under the tutelage of Nikolai Zverev. Rachmaninov would later credit his teacher, Zverev, for turning his ways around and instilling the disciplined work habits which would serve him for life. Despite this reverence for his teacher, Sergei’s studies at Moscow led him to discover a greater passion for composition. His shift in focus on composition angered Zverev and led Rachmaninov to finish his studies with Alexander Ziloti (Sergei’s cousin and a former pupil of Franz Liszt). Rachmaninov studied theory under the great Anton Arensky and Sergei Taneyev. Around this time Rachmaninov was also introduced to Tchaikovsky, who would serve as a profound influence in Sergei’s compositional style. Tchaikovsky commissioned the teenage Rachmaninov to arrange a piano transcription of the suite from his ballet “The Sleeping Beauty”. This commission had first been offered to Siloti, who declined, but suggested instead that Rachmaninov would be more than capable. Siloti supervised the arrangement which became the first of many brilliant and effective transcriptions Rachmaninov would write over the course of his career. On top of all these powerful influences, Sergei learned alongside brilliant classmates including the (now) famous Alexander Scriabin (the early death in 1915 of Alexander Scriabin, who had been his good friend, affected Rachmaninov so deeply that he went on a tour giving concerts entirely devoted to Scriabin’s music). Rachmaninov was a stellar student, completing his piano studies in 1891, one year early. He used his last year to finish his composition course with Arensky by writing the one-act opera Aleko (based on Pushkin’s The Gypsies), which premiered at the Bolshoi Theater in 1893 (the opera remains a staple of the operatic repertoire). For this achievement, Rachmaninov accepted the Moscow Conservatory’s Great Gold Medal as only the third person to ever receive the honor.

The period between 1890 and his emigration in 1917 proved both fruitful and disastrous for Rachmaninov. Frequent summer residencies at the Ivanonka estate (with Auntie Vavara Satina) became a vehicle of inspiration from the endless rolling fields and the solitude he received. Rachmaninov completed many pieces including his First Piano Concerto Opus 1 (1891) and Prelude in C# Minor which was one of the five Morceaux de Fantaisies Opus 3 (1892). The aforementioned Prelude in C# Minor is often referenced to be the composition that put Rachmaninov on the map, both in Russia and abroad. Rachmaninov would (possibly in jest?) exclaim a distaste for his famous prelude since it was so often demanded as an encore at his recitals. In later years he sometimes teased an expectant audience by asking, “Oh, must I?” or claiming an inability to remember it. Despite this, he later wrote two further sets of 10 and 13 preludes respectively, completing the full complement of 24 preludes all in different keys. In 1893 Rachmaninov slipped into a phase of deep depression in response to the death of both Tchaikovsky and Zverev, prompting him to compose the commemorative Trio Elegiaque Opus 9. In 1896 Sergei attempted his First Symphony (Op. 13) and the work was premièred on 28 March 1897 in one of a long-running series of “Russian Symphony Concerts”. Symphony No. 1 was brutally rejected by critics, most notably the nationalist composer César Cui (member of the mighty handful) who likened it to a depiction of the ten plagues of Egypt, suggesting it would be admired by the “inmates” of a music conservatory in hell. P.S. Cesar Cui is the only member of the “Russian Five” whose works are no longer regularly performed… hm. Alexander Ossovsky (side note: he was the cousin of young Ksenia Derzhinskaia (1889–1951) whose successful operatic career as prima donna of the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow was initiated by Rachmaninov) in his memoir about Rachmaninov makes the claim that Glazunov, as a conductor who disliked the work, made poor use of rehearsal time. Other witnesses suggested that Glazunov (widely believed to be an alcoholic) may have been drunk at the event. Regardless of these purported reasons, the premier was a failure and did nothing to help quell Sergei’s dwindling confidence/mental health. One stroke of good fortune came from Savva Mamontov, a famous Russian industrialist and patron of the arts, who two years earlier had founded the Moscow Private Russian Opera Company. He offered Rachmaninov the post of assistant conductor for the 1897–8 season and the cash-strapped composer accepted. During this period he became engaged to fellow pianist Natalia Satina whom he had known since childhood and who was his first cousin. The Russian Orthodox Church and the girl’s parents both opposed their marriage, thus putting a halt to the couple’s plans and adding up to a complete mental breakdown. In 1900, Rachmaninov began autosuggestive therapy with psychologist Nikolai Dahl, himself an amateur musician. Soon after, Sergei reentered the world of compositional renown with the premier of his Piano Concerto No. 2 (Op. 18, 1900–01), dedicated to Dr. Dahl. The piece was very well received at its premiere, at which Rachmaninov was soloist. To top it all off, Sergei found a way to marry Natalia, using the family’s military background to circumvent the church. They were married in a suburb of Moscow by an army priest on 29 April 1902 and his and Natalia’s union lasted until the composer’s death (despite a brief affair with the 22-year-old singer Nina Koshetz in 1916 but we will dismiss such a messy detail). Their happy marriage resulted in the birth of two daughters, Irina (later Princess Wolkonsky (1903-1969)… cool) and Tatiana Conus (1907-1961). After several successful appearances as a conductor, Rachmaninov was offered a job as conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1904. Political reasons led to his resignation in March 1906, after which he chose a cosmopolitan route and stayed in Italy until July. He spent the following three winters in Dresden, Germany, intensively composing, and returning to his old haven “Ivanovka” every summer. The connection to America began when Rachmaninov made his first tour of the United States as a pianist in 1909. For this event Rachmaninov composed the Piano Concerto No. 3 (Op. 30, 1909) as a show piece. These successful concerts made him a popular artist; however, he was unhappy on the tour and declined requests for future American concerts until after he emigrated from Russia in 1917. P.S. this included an offer to become permanent conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

As was the situation for many, the 1917 revolution marked an end of Russian life as Rachmaninov had known it and on December 22nd, 1917 he fled St. Petersburg for Helsinki with his wife and two daughters on an open sled (he carried only a few notebooks with sketches of his own compositions as well as two orchestral scores including his unfinished opera “Monna Vanna” and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Golden Cockerel”). For about a year he hung around Scandinavia performing odd jobs and laboring over new types of repertoire; however, near the end of 1918, he received three offers of lucrative American contracts. Although he declined all three, he began to think that the United States might offer a solution to his financial concerns. Upon arrival in New York on November 1st, 1918, Sergei fast chose an agent, Charles Ellis, and accepted the gift of a piano from Steinway before playing 40 concerts in a four-month period. At the end of the 1919–20 season, he also signed a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company. In 1921, the Rachmaninov family bought a house in the United States, where they consciously recreated the atmosphere of Ivanovka, entertaining Russian guests, employing Russian servants, and observing Russian customs. One of Rachmaninov’s regular visitors was the famous pianist, Vladimir Horowitz. Arranged by Steinway artist representative Alexander Greiner, their meeting took place in the basement of New York’s Steinway Hall, on 8 January 1928, four days prior to Horowitz’s debut at Carnegie Hall playing the Tchaikovsky First Piano Concerto. Referring to his own Third Piano Concerto, Rachmaninoff said to Greiner he heard that “Mr. Horowitz plays my Concerto very well. I would like to accompany him.” For Horowitz, it was a dream come true to meet Rachmaninoff, to whom he referred as “the musical God of my youth … To think that this great man should accompany me in his own Third Concerto … This was the most unforgettable impression of my life! This was my real debut!” Rachmaninoff was impressed by his younger colleague and a bromance was forged of two who were quite supportive of each other’s careers and greatly admired each other’s work. With his many performing engagements, Rachmaninov’s output as composer slowed tremendously. Between 1918 and his death in 1943, while living in the U.S. and Europe, he completed only six compositions. Another, perhaps greater, cause for this drought may have been a timeless case of homesickness. His revival as a composer seemed possible only after he had built himself a new home, Villa Senar on Lake Lucerne, Switzerland, where he spent summers from 1932 to 1939. There, in the comfort of his own villa which reminded him of his old family estate, Rachmaninov composed the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (one of his best known works) in 1934. He went on to compose his Symphony No. 3 (Op. 44, 1935–36) and the Symphonic Dances (Op. 45, 1940), his last completed work. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered the Symphonic Dances in 1941 in the Academy of Music.

A lot of musicians, including myself, will sometimes make the honest mistake of thinking great composers to be superhuman and beyond such mortal concerns as disease. It therefore can come as a shock that even the magnificent Rachmaninov could be subject to the malady of advanced melanoma (a.k.a skin cancer). When he fell ill after a series of concerts in 1942, the family was informed but the composer was not. On February 1st, 1943 he and his wife became American citizens and on February 17th, 1943 Sergei gave his final recital at the Alumni Gymnasium of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville (eerily his program included the famous “Funeral March” by Chopin). A statue called “Rachmaninoff: The Last Concert”, designed and sculpted by Victor Bokarev, now stands in World Fair Park in Knoxville as a permanent tribute to Rachmaninoff. He became so ill after this recital that he had to return to his home in Los Angeles. Rachmaninov lost his battle with melanoma about a month later on March 28th, 1943, in Beverly Hills, California, just four days before his 70th birthday. A choir sang the fifth movement of his “All Night Vigil” (praised by some as Rachmaninov’s finest achievementand “the greatest musical achievement of the Russian Orthodox Church”) at his funeral. He had wanted to be buried at the Villa Senar (his home away from home) in Switzerland, but the conditions of World War II made fulfilling this request impossible. He was therefore interred on June 1st at the Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

After a century of pianists questioning why Rachmaninov would choose to torture their kind, there may be a simple explanation. In addition to his evident virtuosity, Sergei possessed physical gifts including exceptional height and extremely large hands with a gigantic finger stretch (he could play the chord C Eb G C G with his left hand… meaning he could play an interval of a 12th with one hand SUPER IMPRESSIVE). This and Rachmaninov’s slender frame, long limbs, narrow head, prominent ears, and thin nose suggest that he may have had Marfan syndrome, a hereditary disorder of the connective tissue. This syndrome would have accounted for several minor ailments he suffered all his life. These included back pain, arthritis, eye strain (possibly the result of myopia), and bruising of the fingertips. Although Rachmaninov did not suffer the common cardiovascular ailments of the syndrome, studies show that about 40% of Marfan patients will likewise never appear to have this symptom unless echocardiography tests are conducted. Additionally, there is no indication that his immediate family had similar hand spans rendering any familial evidence unlikely. A possible alternative diagnosis of acromegaly, a long-term condition in which there is too much growth hormone and the body tissues get larger over time, may be evidenced by the defining coarse facial features of later photographs. Rachmaninov’s repeated bouts of depression are also consistent with a diagnosis of acromegaly. We will never know for sure if Rachmaninov’s hands were indeed a result of a medical condition; however, if it helps a piano student sleep at night I’m certainly willing to entertain the idea!

Below I have included a hilarious performance that is both amazingly done and witty in that it pokes fun at Rachmaninov’s ridiculous expectations for Prelude in C# Minor:

*You more often see old Rocky’s name spelled Rachmaninoff. I dislike this spelling because it is completely unnecessary. For the Russian spelling of Рахма́нинов (with the exception of the letter “х” which is close to the “ch” we insert in it’s place), each Russian character has an English equivalent (Р=r а=a х=ch м=m а́=a н=n и=i н=n о=o в=v). Oh silly Cyrillic translations…

Awesome Clip from Shosty’s Katerina Ismailova

For those who do not know this great opera by Shostakovich, I thought I would share this clip that I stumbled upon from Katerina Ismailova. Katerina is the epitome of the traditional Russian trophy wife. Ignorant and bored out of her mind, she feels trapped and desperate for real affection in her loveless marriage to Zinovy. That’s where Sergei comes in. He’s the farm hand who got fired for sleeping with his last boss’s wife (you can assume what kind of character this playa playa is).

In this particular scene Sergei is paying a late night visit to Katerina under the nose of her father-in-law Boris and while her husband is away on a business trip. He asks for a book but obviously his real intentions are less innocent…

Consequently Katerina kills Boris by serving him poisoned mushrooms and later she and Sergei kill her husband when he catches them in the act… yeah that’s about the place in the opera where Stalin apparently stormed out of the auditorium in disgust (off to the frozen tundra with Shosty over that one). Then the couple gets caught and sent to Siberia. Sergei dumps Katerina for another labor slave, Katerina loses it, she grabs Sergei’s new girlfriend and pulls the both of them to their death by raging/freezing river.

Well, nobody said Russian married life in the old days was easy…

Real or Not Real: Stravinsky’s Puppet Tale

This time around we delve into the complicated visual and aural spectacle that is Stravinsky’s ballet, “Petrushka” (a.k.a Petrouchka or Петрушка). Like Stravinsky’s other ballet, the Firebird, the plot is decidedly Russian focusing on the traditional Russian puppet (Petrushka), taking place during a carnival celebrating the Maslenitsa (Russian lent), and even featuring a dancing bear (note: bears are a big deal in Russian i.e. the name of the former president, Medvedev is very close to the word “medved” or “bear” resulting in relentless teasing via newspaper cartoons). Petrushka, is a stock character of Russian folk puppetry (a.k.a rayok) known at least since the 17th century. Petrushkas were used as marionettes, as well as hand puppets and were traditionally identifiable as a kind of a jester distinguished by red dress, red kolpak, and often a long nose. Stravinsky began work on the ballet in 1911 and premiered the work at the Théâtre du Châtelet on June 13, 1911 under conductor Pierre Monteux. The production was a feature of the Ballets Russes (The Russian Ballets); an itinerant ballet company from Russia directed by Sergei Diaghilev and widely regarded as the greatest ballet company of the 20th century. Incidentally, the title role was danced by Vaslav Nijinsky, cited as the greatest male dancer of the early 20th century.

Musically the ballet is characterized by a specially created “Petrushka Chord”, consisting of C major and F♯ major triads played together, heralding the appearance of (you guessed it) Petrushka! The ballet as we know and love it today is likely played with the regards to the considerable re-orchestration by maestro Stravinsky that took place in 1947. He purportedly penned the revised version of Petrushka for a smaller orchestra, in part because the original version was not covered by copyright and Stravinsky wanted to profit from the work’s popularity. The ballerina’s tune is assigned to a trumpet in the 1947 version instead of a cornet as in the original. The 1947 version provides an optional fortississimo near the piano conclusion of the original. Stravinsky also removed some of the difficult metric modulations in the original version of the first tableau from the 1947 revision.

In case you were interested…

Compared to the 1911 version, the 1947 version requires: one less flute; two fewer oboes, but a dedicated English horn player instead of one doubled by the fourth oboe; one fewer bassoon, but a dedicated contrabassoon; neither of two cornets, but an additional trumpet; one fewer snare drum and no tenor drum, thus removing the offstage instruments; no glockenspiel; and one fewer harp.

In 1921, Stravinsky created a piano arrangement for Arthur Rubinstein entitled Trois mouvements de Petrouchka, which the composer admittedly could not play himself for lack of adequate left hand technique.

An interesting cultural aside, the Russian Children’s Welfare Society (RCWS) hosts an annual “Petrushka Ball”, named after Stravinsky’s star-crossed Petrushka who fell in love with the graceful ballerina.

Here is a recap of the plot:

The ballet opens on St. Petersburg’s Admiralty Square during the celebratory Shrovetide fair (a Russian Mardi Gras if you will). An organ grinder and two dancing girls entertain the crowd to the popular French song “Une Jambe de Bois” (notice the reference to the French, reflecting Russia’s obsession with French culture) before giving way to drummers introducing the enchanting Charlatan (magician). To the amazement and curiosity of the crowd, The Charlatan plays a short diddy on the flute, bringing to life three puppets that then proceed to dance a rigorous Russian Dance. Of these puppets is (obviously)”Petrushka”, a rather uppity “Ballerina” (more on this later), and a “Moor” (unfortunately the character was traditionally performed by a white dancer painted in black face, causing quite the racial uproar… this is beside the point).

Following this joyous performance, the mood becomes considerably darker when we are taken to the scene of Petrushka’s backstage prison. The walls are painted in dark colors and decorated with stars, a half-moon and jagged icebergs or snow-capped mountains. With a resounding crash, the Charlatan kicks poor Petrushka into this barren cell. Through some virtuosic and often, well, interpretive choreography we learn that Petrushka is magically possessed with human feelings including bitterness toward the Charlatan for his imprisonment as well as love for the beautiful Ballerina. To add insult to injury, a frowning portrait of his jailer hangs above him as if to remind Petrushka that he is a mere puppet. The understandably indignant clown-puppet shakes his fists at the portrait and then proceeds to attempt escape from his cell but, alas, he fails pathetically. This is about the time the Ballerina enters randomly through the door (I think we are to believe the magician sends her in?). Petrushka tries to impress her and share his true feelings but she cruelly disregards all his gestures of adoration. Apparently, even as they are entrapped in the same cell, Petrushka is too low for miss high and mighty on the totem pole.

Next the audience is transported to the far superior, spacious, and lavishly decorated room of the Moor. Rabbits, palm trees and exotic flowers decorate the walls and floor. The Moor reclines on a divan and plays with a coconut, attempting to cut it with his scimitar. When he fails he believes that the coconut must be a god and proceeds to pray to it… what? Anyways, the Ballerina again magically appears but this time her attitude is transformed. Attracted to the Moor’s handsome appearance she plays a saucy tune on a toy trumpet and dances a happy jig (is it me or is this character just more unlikeable by the minute?). Petrushka finally breaks free from his cell, and he interrupts the rather embarrassing seduction of the Ballerina. Petrushka attacks the Moor but soon realizes he is too small and weak. The Moor beats Petrushka. The clown-puppet flees for his life, with the Moor chasing him, and escapes from the room. So basically the bigger, prettier, shallow character gets the girl while poor Petrushka, with a heart burdened by hopeless unrequited love, is defeated in spectacular fashion. Not sure this is a great lesson to take home to the kids…

In the final scene we are again brought to a festive scene at night, complete with an array of apparently unrelated characters including the Wet-Nurses (who dance to the delightful tune of the folk song “Down the Petersky Road”), the peasant with the previously alluded to dancing bear, a group of a gypsies, coachmen, grooms, and masqueraders. Suddenly a frightened Petrushka runs across the stage, followed by an irrationally violent Moor brandishing his sword, and finally the Ballerina who watches in horror from the sidelines. The crowd is ablaze with outrage when the Moor catches up to Petrushka and slays him with a single blow. The police question the Charlatan about the apparent murder but in a rather reasonable move the magician holds the “corpse” above his head, shaking it to remind everyone that Petrushka is but a puppet. Satisfied, the crowd dissipates and the Charlatan begins to tow away the ruins of his property. All of a sudden, Petrushka’s ghost appears on the roof of the little theatre, his cry now in the form of angry defiance (to really drive the point home, Petrushka’s spirit thumbs its nose at his tormentor). Now completely alone, the Charlatan is terrified to see the leering ghost of Petrushka. He runs away whilst allowing himself a single frightened glance over his shoulder. The scene is hushed, leaving the audience to wonder who is “real” and who is not. Hm…

Allow me to include a youtube presentation of the ballet. If the plot is a little wacky, the music is extraordinary and the choreography is very eye catching:

Prokofiev Loves His Three Oranges

This time around we will visit one of our favorite little Russian Geniuses, Sergei Prokofiev (OK fine he was technically Ukranian, but most music historians still consider him to largely be an important Russian composer), and talk about his most famous opera, “The Love of Three Oranges”. This work of art is charming as it is witty in making fun of the government officials without being outright scandalous.

Although the opera pokes fun at that powers that be in Russian it is important to make the distinction that this Opera was written originally in America for a Chicago audience. In 1918 Prokofiev was allowed to travel to the USA in hopes that he would spread the word about the success of Russian art in America. Needless to say this trip went swimmingly. After presenting a recital including the famous Piano Concerto No. 1, performed by the composer himself, Prokofiev caught the eye of Cleofonte Campanini(principal conductor and general manager of the Chicago Opera). He awarded Prokofiev a commission to compose a new opera for the company and thus the work in progress Prokofiev had in his repertoire was completed, “The Love of Three Oranges”. Although this opera does have a Russian libretto, it would have been quite inappropriate to present a Bolshevik themed opera in the Russian language to an American audience, thus the libretto was translated and premiered in French.

The plot of this opera by nature makes little sense and is more importantly meant to entertain through the use of satire. Just FYI, it is based on an old Italian Fairy Tale. Well here goes…

Act 1:

The King of Clubs and his adviser Pantalone are worried about the health of the Prince, a hypochondriac whose symptoms have been brought on by an indulgence in tragic poetry. Apparently his ailment can only be cured with laughter, so Pantalone summons the jester Truffaldino to arrange a grand entertainment, together with the (secretly inimical) prime minister, Leandro.

The magician Tchelio, who supports the King, and the witch Fata Morgana, who supports Leandro and Clarice (niece of the King, lover of Leandro), play cards to see who will be successful. Tchelio loses three times in succession to Fata Morgana, who brandishes the King of Spades, alias of Leandro.

Leandro and Clarice plot to kill the Prince so that Clarice can succeed to the throne. The supporters of Tragedy are delighted at this turn of events. The servant Smeraldina reveals that she is also in the service of Fata Morgana, who will support Leandro.

Act 2:

All efforts to make the Prince laugh fail, despite the urgings of the supporters of Comedy, until Fata Morgana is knocked over by Truffaldino and falls down, revealing her underclothes — the Prince laughs, as do all the others except for Leandro and Clarice. Fata Morgana curses him: henceforth, he will be obsessed by a “love for three oranges.” At once, the Prince and Truffaldino march off to seek them. Yeah really…

Act 3:

Tchelio tells the Prince and Truffaldino where the three oranges are, but warns them that they must have water available when the oranges are opened. He also gives Truffaldino a magic ribbon with which to seduce the giant (female) Cook (a bass voice!) who guards the oranges in the palace of the witch Creonte.

They are blown to the palace with the aid of winds created by the demon Farfarello, who has been summoned by Tchelio. Using the ribbon to distract the Cook, they grab the oranges and carry them off into the surrounding desert.

While the Prince sleeps, Truffaldino opens two of the oranges. Fairy princesses emerge but quickly die of thirst. The Ridicules (Cranks) give the Prince water to save the third princess, Ninette. The Prince and Ninette fall in love. A body of soldiers conveniently turns up and the Prince orders them to bury the two dead princesses. He leaves to seek clothing for Ninette so he can take her home to marry her, but, while he is gone, Fata Morgana transforms Ninette into a giant rat and substitutes Smeraldina in disguise.

Act 4:

Everyone returns to the King’s palace, where the Prince is now forced to prepare to marry Smeraldina. Tchelio and Fata Morgana meet, each accusing the other of cheating, but the Ridicules intervene and spirit the witch away, leaving the field clear for Tchelio. He restores Ninette to her natural form. The plotters are sentenced to die but Fata Morgana helps them escape, through a trapdoor and the opera ends with everyone praising the Prince and his bride

I warned you…

Anyways Below is a recording of one of my personal all time favorite compositions, the “March” from “The Love of Three Oranges”!

Shostakovich’s Great Big Serious 9th Symphony… PSYCHE!

I always love an opportunity to present the great Dimitri Shostakovich as the mastermind he is. His Symphony No. 9 is most def. a case in point!

Educated music historians are aware of the so-called composer’s curse. Beginning with the late Ludwig Van Beethoven, it seemingly became a pattern that upon the completion of his ninth symphonic masterpiece a composer would croak. This is evidenced in the death of Schubert, Bruckner, Dvorak, Mahler, and Vaughan Williams who all died within weeks of reaching this ill fated number in their composition repertoire… ok so maybe this is a bit of an over simplification but the point is that #9 is a significant number to the “greats” who followed in their predecessor’s footsteps.

When it came time for Shostakovich to write his Symphony No. 9, the Russia music community was practically teeming with excitement over the possibilities Shosty would explore in his music. Many expected him to pull out the big guns and write a symphony to include choir like the massive Beethoven counterpart. These suspicions were bolstered by the composer’s declaration in October 1943 that the symphony would be a large composition for orchestra, soloists and chorus which the context would be “about the greatness of the Russian people, about our red army liberating our native land from the enemy (the Nazi’s)”. The government who had their fingers in all matters of art (because government officials surely know everything about everything when it comes to evaluating music) expected a nationalistic wonder full of serious sentiment and dignity. Of course they were all woefully disappointed…

Despite initial sketches presented by Shostakovich in April of 1944, he ultimately lost inspiration for his originally intended work. Following a long break, during which he dropped the project completely, he resumed working and finished the real Symphony No. 9 on August 30th, 1945. This symphony turned out to be a completely different work from the one he had originally planned, with neither soloists nor chorus and a much lighter mood than expected. He forewarned listeners, “In character, the Ninth Symphony differs sharply from my preceding symphonies, the 7th and the 8th. If the Seventh and the Eighth symphonies bore a tragic-heroic character, then in the Ninth a transparent, pellucid, and bright mood predominates.”

As predicted by Shostakovich himself, many of his colleagues praised the symphony as charming and overall successful, whereas the government critics believed it to be “Ideologically weak” and “misrepresenting of the Soviet attitude”. Surprisingly the West reacted unfavorably as well, believing it to be a childish celebration over the defeat of Hitler. This was a very tender time for the world so certain considerations for their error in judgment can be excused… Symphony No. 9 was nominated for the Stalin Prize in 1946, but failed to win it. By order of Glavrertkom, the central censorship board, the work was banned on 14 February 1948 in his second denunciation together with some other works by the composer. It was removed from the list in the summer of 1955 when the symphony was performed and broadcasted.

In Beethoven-like fashion, the entirety of the work spans 5 mvts (note: the Beethoven 9th Symphony is technically four movements but the nature of the fourth movement lends itself to being broken in two parts making it seem as if it were five movements) . On a personal note I have recently performed this Symphony and have found it to be delightful. It is sweet and joyful while still retaining that creepy tombstone quality that is found in all music of Shosty (he dedicated the entirety of his works to the thousands who were killed in Stalin’s purges). My favorite moment would certainly be the theme in the first mvt. played as a violin solo (In my performance our concertmaster/violin soloist was a tall blond Russian guy by the name of Igor Kalnin so I couldn’t help but bask in the awesomeness)!

Below I am including a video of said 1st Mvt:

Glamorous Glinka

Most incorrectly, many people regard Russian Music pre-westernized to be just about non-existent. If you review my past post on the “History of Early Russian Music” you will surely realize the error of your ways and be enlightened. However, I can recognize a clean revolution in Russian music history at the beginning of the 19th century when the east met the west. For the purposes of this blog, I will introduce you to the composer that many music historians refer to as “the first important Russian composer”, Mikhail Glinka.

The early life of Glinka was, well, privileged. Born (June 1st, 1804) to a high-ranking military family in service of the Tsar, Glinka enjoyed an easy childhood of sweets, furs, and a doting babushka. He was so coddled that indeed he developed a fragile disposition and remained in frail health throughout his life. Glinka was often exposed to Russian Folk music via traveling musicians. He heard the church bells tuned to dissonant chords, thus shaping his early understanding of harmony. Glinka was lucky enough to have had a private teacher who introduced him to Russian, German, and French language as well as their respective geographies. This also put him in touch with the popular western style music that he studied as a pianist and violinist. At 13 Glinka was sent to St. Petersberg to study under the piano professor Charles Meyer and it was not long before the young Glinka was recognized as a virtuoso. In 1830 he was even taken on a meandering tour through Italy where he took lessons at the conservatory in Milan (this was the thing to do if you were an up and coming composer in Russia because even its own people disregarded their own music for some misguided reason). Obviously this trip had a profound effect on the development of Mikhail’s musicality; however, Glinka fast became disenchanted with the Italian ways as he recognized that his duty was to his homeland in Russia and Russia’s own music culture.

In 1834, when Glinka was in Berlin, he received a fateful message that his father had died. This prompted him to return to his hometown in Novospasskoye. While in Berlin, Glinka had become enamored with a beautiful and talented singer, (for whom he composed Six Studies for Contralto). He contrived a plan to return to her, but when his sister’s German maid turned up without the necessary paperwork to cross to the border with him, he abandoned his plan as well as his love and turned north for Saint Petersburg. There he reunited with his mother, and made the acquaintance of Maria Petrovna Ivanova. After courting her for a brief period, the two married. The marriage was short-lived, as Maria proved to be utterly without tact and uninterested in his music. The silver lining here is that Glinka used his nagging ex-wife as inspiration for his most famous opera “A Life for a Tsar”.

The significance of “Ivan Susanin” (the original title for “A Life for a Tsar”) lies in the fact that this was the first Russian Opera sung in Russian Language. The work was premiered on December 9, 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos, who had written an opera on the same subject in Italy. Although it still retained a plethora of characteristics distinctly European, Glinka’s work was a grand success. In essence, he paved the way for future Russian composers (including of course the “Russian Five”) who would dedicate their lives as composers to writing Russian nationalist music in the traditional style.

Glinka lived his last years in Berlin. He died suddenly on 15 February 1857, following a cold. Glinka was buried in Berlin but a few months later his body was taken to Saint Petersburg and reinterred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

Below I am including a recording of Glinka’s Grand Sextet for piano, two violins, viola, cello and double bass. You’re welcome 🙂

The East Meets the West: 18-19th Century Russian Music History and the Rise of Glinka (a research paper by Courtney Van Cleef)

*I did not include my bibliography nor are my sources cited in this online posting!

Despite Russia’s rich musical life (demonstrated in the volumes of folk-songs that date back hundreds of years), Russia is a country whose music history is largely abandoned before the 18th century. In fairness, the separation between the Roman Catholic Church and the Russian adopted Eastern Orthodox Church can be largely to blame for the gap in time before Russian music arrived on the western radar. Unlike the extensive rise of the Mass that catapulted change in Europe, the Eastern Orthodox Church imposed strict restrictions on its music rituals, thus thwarting development such as the kind observed in the west. Towards the end of the 18th century, however, Russia began to see great changes in its political atmosphere. The Tsars, particularly Tsarist Catherine the Great, suddenly adopted a sincere interested in the affairs of their European neighbors. The opening up of this previously isolationist society naturally led to a demand for western art and all its modern trappings in opera, dance, and instrumental music. Under these circumstances, it was to be that Russian music would finally escape obscurity and eventually (in the 19th century) begin its own historically significant developments as a unique nation. Success was mainly achieved through the prevailing musical movement of the time, “nationalism”. This paper aims to examine the events of late 18th century and 19th century Russian music history, including its historical context, the construction of a new music society, and the rise of Russia’s first significant composer (in western terms) Mikhail Glinka.

In order to understand Russian composers of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the “romantic era” in terms of music, one must first understand what was happening in the surrounding world at the time.

Following the Napoleonic wars, Europe (including Russia) became a region of great instability due to its disruption of previously established borders. In order to assist in the reduction of tensions, the leaders of all the major states of the time convened to Vienna for the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815).

The goals of the Congress of Vienna were to mainly restore the status quo of powers before 1792 without punishing France. This was in order to prevent revenge and hostility from the French people. The main powers to convene included Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and later France. Although the meeting did accomplish its immediate goals to scale back France’s conquests and return to its 1792 borders, it tragically failed to address the cultural borders of the individual states. For example, Russia’s prized acquisition as a result of the meeting included the Duchy of Poland, regardless of Poland’s clear cultural distinction from Russia. Such violations prompted an attitude of rebellion by the people that would ultimately lead to World War 1.

The important consequences of these tensions in art were the rise of nationalism. The basic sentiment was that a citizen owed his/her loyalties to his/her nation before government, creed, dynasty, etc. In music the folk music was considered higher than all other national music as it is most closely related to the people. An important thing to note is that while the beginning of the nationalist movement began as people who identified themselves as citizens of a larger world, it later turned into a much more aggressive and almost competitive attitude of people aligning themselves with specific identities. Also important to mention is that although nationalism in theory refers to all classes of people within a society, the movement was entirely a movement of the bourgeois in order to establish their patriotism. Although nationalism affected different regions in different ways, Russia is unique in that its revolution during the 19th century failed to displace the Tsar and lead to democracy. The music lends itself to more themes of monarchy and the other popular practice of nationalism including exoticism. In reference to the Tsar’s power over nations in central Asia, many Russian composers wrote their music

with exotic Asiatic themes that distinguish their works as uniquely Russian.

As many of the Romantic composers turned to folk music as a center piece of their compositions, it became necessary that the music change to accommodate the flavor to such old tunes. Since folk music is largely monodic and does not fit cleanly into the harmonic structures defined during the classical era, composers were forced to explore new tonalities and move away from the traditions that had dominated in Italy, France, and Germany, for centuries. For example, most Russian folk music contains a dubious tonic and employs generous amounts of parallel 5ths, octaves, and other dissonant parallel intervals. Whereas music previously imitated earlier works, and borrowed from previous success, it was now considered inauthentic to engage in such practices and composers were pressured to conceive of entirely new and unique ideas. As previously mentioned, the nationalist movement was largely identified by the more educated bourgeois and ironically, its authenticity and folk characteristics were generally lost on the less sophisticated audiences from which they supposedly drew their inspiration.

Specifically, the Russian nationalist music began the process of unearthing its roots in its first printed collection of Russian folk songs by Chulkov. With appearances of his work beginning to appear from 1770-1774 under the title of “Sobraine Raznukh Pesen”, the entirety of Chuklov’s collection was organized in four volumes. Unfortunately, however, the collection was primitive and made little to no attempt in dividing the mass of folk songs by genre. Nonetheless, the 800 pages of text containing over 400 peasant songs either from existing manuscripts or indeed written out by Chuklov himself, established a pattern for future Russian folk-song collections into the 19th century. Finally a more organized and systematic collection was realized in the “Collection of Russian Folk Songs” assembled by Nikolai Lvov and written out by Ivan Prach in 1790. Unlike the collection of Chuklov, the Lvov-Prach collections was perhaps the first collection to extensively divide and classify folk songs into the categories “protracted songs, dance songs, wedding songs, Khorovods, Christmas carols, and Ukranian songs”. Main contributions of this anthology also demonstrate features of the peasant chant including “shifting tones and uneven rhythms that would become prominent features of Russian musical style from Mussorgsky to Stravinsky”; however, the songs are adapted to western musical traditions in order to be more pleasing to the ears of Russia’s “piano-owning classes”. “Despite its inaccuracy, Lvov-Prach’s work provides many important insights into transcription methods, classification criteria, and theories that explain what exactly separates Russian music from its western counterparts”. As a result many of the “original folk tunes” used in nationalistic repertory are taken from the Lvov-Prach collection. In essence it paved the way for more skilled arrangers (for example, Balakirev and Rimsky- Korsakov) to revive their rich musical heritage.

Before diving into the significant literature of the 19th century, it is necessary to examine one more significant historical development, the appearance of Italian Opera from 1731 and onward. Like all Russian music, once again the tradition dates back to encounters with the all-encompassing western art of opera, derived from Italy. In 1736, St. Petersburg was presented her first fully staged production of Francesco Araja’s “The Power of Love and Hate”. The theatrics combined with the western musical style that was becoming increasingly popular in Russia dazzled its audience with its grandness. The opera was naturally sung its original Italian. It was not until 1755 that an opera was finally translated to the Russian mother tongue and acted out by young Russian native performers. The first opera “Cephalus and Procris”, translated by Sumarkov, was merely rearranged by its original Italian composer, Araja, and thus failed to change fundamentally to include Russian national themes to match its changed Russian libretto. Well into the 18th century, Russian opera continued to be written by foreign composers, though in in the last year folk elements finally began to appear in the material. Seaman reports that “of about 100 operas written in the course of the last years of the 18th century, 30 survived 15 of which make use of Russian or Ukrainian Folk music”. More specifically these operas employ a total of about “55 clearly identifiable folksongs”. Evidence suggests that the first Russian

opera written by a native composer on a native topic was “Anyuta”. Musicologists speculate that a man by the name of Pashkevich composed the opera, though the music itself is tragically lost and thus it is difficult to determine definitively. Important to note, despite all attempts to produce authentically Russian opera of high quality, efforts were largely hindered by a lack of trained native musicians capable of delivering technically challenging performances.